September 16, 2020

So much of the official and public ecumenical life of the churches today revolves around theological considerations that, at times, we risk forgetting the role of the personal in ecumenism. With each decade of experience in church unity work I have become more and more convinced that, no matter how important theological work is for reconstituting unity, the real crux for the ecumenical movement is to preserve and deepen the experience of unity on the local level. Theological consensus will open the door to church unity, but the only thing that will get us through that door is growing together in newly discovered fellowship and commitment.

When we get to know one another on a human level, a trust is born that enables us together to broach the most sensitive subjects in a spirit of mutual respect. The Christ in me warms to the Christ in the other. And the closer we draw to the center of our faith lives, the closer we draw to each other.

The quest for Christian unity began when seemingly providential circumstances brought friends together. For example, a book by Anglican Rev. Spencer Jones, entitled England and the Holy See, evoked an extensive correspondence with Fr. Paul Wattson, founder of the Graymoor Atonement Friars who began the original Week of Prayer for Christian Unity Octave. Their friendship became, in the words of Wattson, “the seed-thought of the Octave.” Could there be a more fitting symbol of what God can do through persons open to the grace of Christian friendship and committed to pursuing the common good?

The significance of friendship with members of other churches holds some important implications for the way we do our tasks together. For example, ecumenical gatherings need to build into the schedule time that encourages social inter-action between people. The coffee break or social hour before dinner may have more significant impact in bridge-building than the long theological discussions that went on during the afternoon formal dialogue.

Church representatives have often experienced how a conversation in a bus from the airport to the hotel where a conference is being held, or chatting after a meeting while waiting for a flight, can result in collaboration months later. The subject discussed may have no relationship to the conference or dialogue theme, but the personal contact sets up a climate of trust that is the safety net for the whole ecumenical enterprise.

The last 30 years have seen a wonderful array of formal statements of agreement between churches. But like so many seeds, they will be effective only if the ground has been prepared. That ground is the people of the various churches that have sponsored the process leading to the agreed statements. Now that the theologians have done their work, the baton is passed to the churches’ membership at large. The first order of business on the next decade’s agenda calls for members of different churches to share their life and faith at the local level. They must have the opportunity to come to the same conclusions as did those who officially represented them in the dialogues.

People who have been living next door to each other, attending town, neighborhood or school meetings together, mixing socially in living rooms and backyards, are now called upon to expand their sharing of life to include a sharing of faith, to discuss what they hold in common as Christians and how they can learn from what separates them. By thus serving one another and sharing spiritual resources, we will be building up the body of Christ from below, from the grassroots level. With the living stones of our lives, we will build a spiritual house.

All the doctrinal agreements arrived at in formal dialogues between the various churches will come to nothing if there is no commitment to one another at the level of the local congregation, if there is no community-building from below. Clearly, nothing is going to happen ecumenically without it. On the other hand, once the church-dividing doctrinal disagreements are resolved, it makes no sense at all to think that people in local parishes who have made a deep commitment to one another, who together have praised God and shared their lives with one another, are going to say no to reunion.

In our Sunday assemblies, do we pray by name for our neighboring Christian communities, thereby witnessing to a sense of real though imperfect communion in faith with them? When we relax and socialize as a faith community, do we extend an invitation to the congregation down the street to join us in our picnic so we can get to know one another? When we respond to the gospel mandate for peace and justice, do we pool our resources with our Christian neighbors and do it together?

The World Council of Churches meeting in Lund, Sweden established a principle for the normal operating procedure of each church: “Do everything together as far as conscience permits.” If you stop to think about it, there are very few things conscience obliges us to do separately. We need each other’s insights to correct deficiencies and imbalances. This approach does not undermine the confessional loyalty of the people concerned, but makes them appreciate the strength of the diverse traditions.

In the years ahead, we Christians must learn to be both hosts and guests. To be hosts, we must be firmly rooted in a particular tradition of response to the gospel and therefore have a home into which we can welcome another for reflection together, for speaking and listening. And to be guests, we must be ready to go where the other lives, to see and understand the way things are done in the other’s household.

Before us is the challenging task of giving an increasingly visible witness to the gospel of reconciliation which we commonly claim and which together we seek to preach and serve. What might we do together? Here are 9 Action Ideas:

- Gather together congregational leaders in your neighborhood for a daylong meeting to discuss joint activities in worship, education, or service.

- Celebrate with other congregations on occasions like The Week of Prayer for Christian Unity, World Day of Prayer, Reformation Sunday.

- Exchange preachers for one Sunday with another congregation.

- Sponsor joint studies on issues such as racism, economic justice, hunger, human rights.

- Share audio-visual and Christian literature resources.

- Initiate service projects among area churches to respond to needs such as housing, unemployment, transportation for the elderly and handicapped, and care for refugee families.

- Organize cluster youth ministries.

- Hold workshops on other world religions and traditions from other cultures.

- Pray for each other. Pray for the unity of the followers of Jesus.

Some of these Action Ideas may not be appropriate during this time of pandemic and social distancing, but some are possible. Choose one and plant the seed.

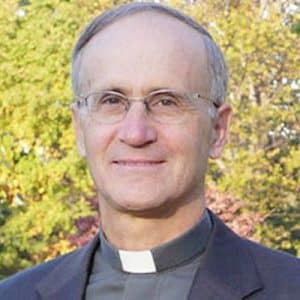

Tom Ryan, CSP, directs the Paulist National Office for Ecumenical and Interfaith Relations located in Boston.