October 21, 2020

Paulist Fr. Rich Andre preached this homily for the 29th Sunday of Ordinary Time (Year A) on October 18, 2020 atSt. Austin Catholic Parish in Austin, TX. The homily is based on the day’s readings: Isaiah 45:1, 4-6; Psalm 96; 1 Thessalonians 1:1-5b, 19-20; and Matthew 22:15-21.

Today’s gospel passage ends with Jesus saying, “repay to Caesar what belongs to Caesar, and to God what belongs to God.” Despite studying this passage at length, I still don’t know what Jesus means!

I do know, however, about the circumstances surrounding this passage. This is the fourth week in a row we’re been with Jesus in the Temple area after his triumphal entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday in the Gospel of Matthew. Tensions are rising, and the question placed before Jesus is controversial: should Jews pay the Roman census tax? Pharisees opposed the tax, but they feared to say so publicly. (Matthew’s readers know that the opposition to this tax eventually led to the destruction of the Temple in the year 70 AD.) But the Pharisees invite some Herodians – Jews who collaborated with the Romans – to be part of the crowd, so that no matter what answer Jesus gives, part of the crowd will be infuriated.

How is the Church supposed to relate to the state? Can we accept God’s declaration in Isaiah that Cyrus, the pagan king of Persia, is God’s anointed agent? As Paul greets the Thessalonians with wishes of grace and peace, let us pause and celebrate God’s mercy.

Was it right to pay the census tax? It was required of everyone in the Roman Empire. Many Jews opposed paying it.

In fact, the Pharisees were opposed to most of the coins used in the empire. Those coins bore the image of the emperor Tiberius Caesar, and because Roman considered Tiberius to be a god, the Pharisees considered coins with Tiberius’ image to be idolatrous. That is part of the reason why money changers were needed in the temple area – so that Jews who had Roman coins could change them into Hebrew shekels for paying the Temple tax. In Jesus’ time, however, the Roman empire accommodated the Jews’ religious concerns, so they made Roman coins for Jews to use that did not bear the image of Tiberius Caesar.

Jesus is brilliant not so much in what he says as in what he shows. These particular Pharisees – who claimed to be so pious – not only had brought Roman coins into the Temple area, but they had carried in coins with the idolatrous image on them.

Jesus seems to endorse paying the Roman census tax. Even these Pharisees – with serious objections about the Roman occupation of Jerusalem – had to use Roman coins in order to negotiate day-to-day living there. So, when Jesus says to repay to Caesar what belongs to Caesar, and to God what belongs to God, I don’t think he’s saying that Church and State can or should be completely divorced from one another. All things belong to God; some things also belong to the state.

How do we determine our exact responsibilities to the state? Even if Jesus had said something applicable to the people who were listening to him – people whose great-grandparents belonged to a weak, patriarchal theocracy that had now been occupied for a century by a far-off pagan empire that did not recognize civil rights for women and slaves – Jesus’ words would probably not apply to our representative democracy that recognizes religious freedom. Let’s also remember: at the time that Matthew is writing his gospel, his audience remembers that just 10-15 years earlier, the Jewish opposition to the Roman census tax led to the destruction of all Jerusalem, including the Temple where Jesus is speaking.

So, what are we to make about the relationship between church and state in the United States today? The Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment to the Constitution say, ““Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” We often refer to this as “the separation of church and state,” but that phrase is misleading. One friend explains: “the principle is that the state should be a disinterested party, not an uninterested one.” Throughout the history of our nation, people have tried to push the Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses in two different directions. There are people who are pushing for the government to grant a particular faith favor over other religions, or over those who practice no religion. Considering that even God dictated that the ancient Israelites needed to protect and care for the aliens within their midst, such religious favoritism would be problematic in the United States. Another friend puts it this way, “The United States should not be considered a ‘Christian’ nation any more than it is a Jewish nation, a Muslim nation, a Hindu nation, or a Buddhist nation.” On the other hand, some people argue that religious concerns should have no influence whatsoever on governmental deliberations: that all religious beliefs should be checked at the door. That argument is also problematic, as the government is constantly making decisions about morality, and the world’s great religions have engaged in the deepest studies of determining right from wrong. People who participate in the world’s religions can’t easily leave that part of themselves out when making decisions regarding voting, leadership, and legislation.

Two weeks ago, the world received a great gift in helping us consider how Church and State can appropriately interact with each other. Pope Francis released his second major encyclical,1 called Fratelli Tutti. As his previous encyclical (Laudato Si’) was about our obligation to care for the environment, this encyclical is about our obligation to care for all our sisters and brothers. Francis lays out principles regarding forms of government, ethical government policies, and the duties of all governments to care for the common good. Like most of Francis’ writings, Fratelli Tutti is engaging to read and challenging to our values.

It is no coincidence that Pope Francis released the encyclical on the Feast of St. Francis, with a title taken from the writings of St. Francis. Just as St. Francis visited the Egyptian sultan, Malek al-Kamil, during the Crusades in the year 1219 to discuss interfaith conflict and the possibility of peace, Pope Francis visited the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar, Ahmad El-Tayeb, exactly 800 years later. Together, the pope and the imam signed the “Document on Human Fraternity.”

The new encyclical is Francis’ expansion of ideas in that earlier document, but the main message is the same: we are not our own. As Francis writes,

The Church, while respecting the autonomy of political life, does not restrict [its] mission to the private sphere. On the contrary, “[we] cannot and must not remain on the sidelines” in the building of a better world, or fail to “reawaken the spiritual energy” that can contribute to the betterment of society.2

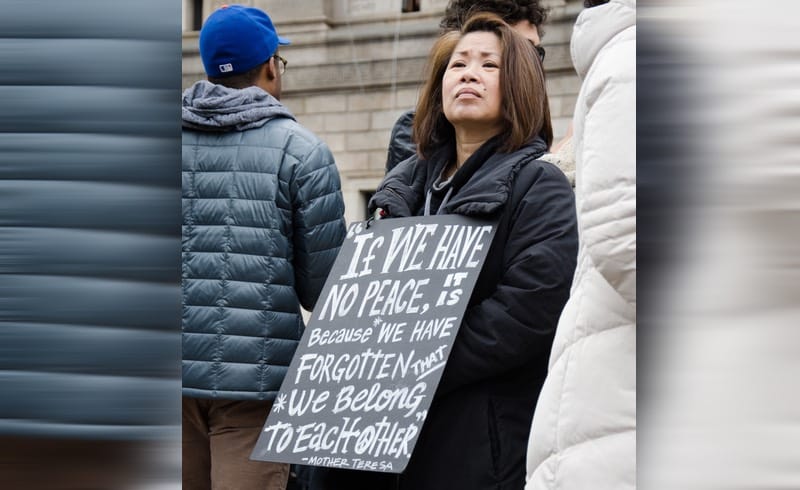

Or, to summarize all of Fratelli Tutti into 5 words: We belong to one another.

With that said, what belongs to God? What belongs to Caesar? What belongs to the federal government? What belongs to the state of Texas? These questions call for constant discernment on our parts, in cooperation with the Holy Spirit… and now, with an assist from Pope Francis. But one thing is clear: on Earth, matters of Church and State are neither coterminous nor completely disconnected. We all have a responsibility, as sisters and brothers of good will, to build up the kingdom of God in all that we do.

Notes:

- This is actually the third encyclical released by Pope Francis. The first, Lumen Fidei, was released shortly into Francis’ pontificate. It was largely written by Pope Benedict before he resigned from the papacy, with Francis making only minor revisions. ↩

- Fratelli Tutti, 276. ↩